2. ANTHROPIC ACTION

While the complex evolution over the centuries of anthropic frameworks on the one hand progressively reduced the free expansion of natural dynamics, it also established an interesting anthropic morphology to exploit opportunities offered by rivers. From archive sources, there emerges a very close relationship between the hydrographic network and socio-economic dynamics, with special regard to the progress of hydraulic engineering, aimed at the agronomic reclamation of vast marshland strips, with the actual construction of man-made countryside. This involved design and operative phases, and subsequent physiological results that went beyond the mere production environment and residential areas, extending to the cultural processes of symbolic elaboration that justify, celebrate and explain the role of the community in environmental evolution. Another important consideration is the consolidation of social perception marked by definite and shared aesthetic tastes in the appreciation of the river landscapes. These are seen as evocative heritage scenes, expressing the complex interaction of natural conditions and human intervention, which in the entire western culture constitutes one of the most recurrent iconic themes found in landscape painting [Gibson, 1989]. The construction of a specific amphibious imagery as the basis for reading into the hinterland of Venice in fact finds its utmost expression in the iconographic evolution of Veneto painting from the end of the 15th century. Here, drawing from the potential of prospective studies, great importance was attributed to the reproduction of accurate landscapes providing the background to the predominant religious scenes. And among the outlines of landscape features found in the canvases of Giovanni Bellini, Cima da Conegliano, Giorgione through to Jacopo Bassano there are widespread references to brooks, river banks, rivers, lakes, and also ports, cities, mills and barges, which, in the acclaimed frescoes attributed to the school of Paolo Veronese, decorating the main floor of the villa of Barbaro in Maser, can even be seen as a virtual typological report of specific hydraulic and geographic features (fig. 9).

2.1 Navigation in the Venetian era

Nautical relations on Veneto terra firma should not only be related to the specific complexity of the hydrogeographic network, but also with the well distributed presence of modestly sized residential settlements, mostly located near the banks of a natural river or major and minor artificial canals. While major river navigation routes existed, connecting the main inland centres with the quaysides of Venice, representing a fundamental and strategic interface between the trade routes to central Europe and the flow of superior goods from the East, there were also important routes in the direction of Lombardy, Emilia and Friuli, and an equally important dense network of secondary connections making up the minor hydrographic network. The latter was a predominantly local based system of relations (not always well documented), where the practice of navigation involved short haul transport, within a single day, most frequently related to the daily needs of riverside life style (transfers from one side of the river to the other, fishing and hunting, collection of marshland herbs and reeds, domestic transport), rather than longer haul traffic.

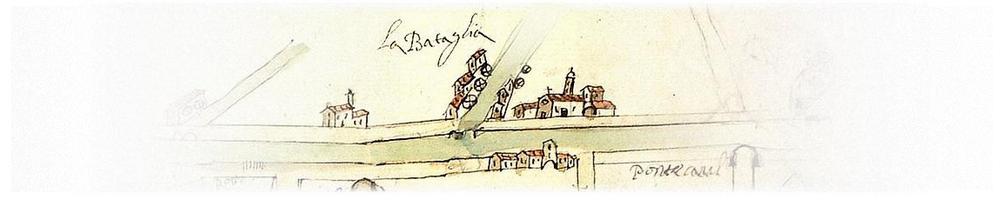

The entire Stato da Tera (mainland domain), through to the innermost river sides where goods delivered here by water were transferred from boats to carts for subsequent destinations, was thus marked by a series of ‘land streets, rivers and minor waterways, an immense networks of regular and fortuitous connections, for perpetual distribution, with a virtually organic circulation.’ [Braudel, 1986, p. 282]. There is a wealth of cartographic documentation between the 16th and 18th century testimony to the crucial amphibious territoriality between the Euganean Hills and the southern end of the lagoon, and revealing a thriving system of navigation routes which, aside from the frequently used route between Battaglia and Chioggia, also involved modest rural villages such as Pernumia, Cartura, Cagnola, Bovolenta, and Correzzola, and larger towns such as Piove di Sacco, connected to the lagoon by the Fiumicello canal. There follows an important aspect, in perfect harmony with the objectives of this study, which is the recognition of all that remains today of the minor hydrographic network used in past centuries as a system of neighbouring relations. These were effectively infrastructures with significant and articulate physical features, wherein the navigable routes, intersecting with the aims of reclamation and irrigation, show the intrinsic features of a superior and amphibious landscape.

In fact, through to the widespread use in the late nineteenth century of the steam-powered water pumps for mechanical pumping of water, large areas in the low plains examined here had permanent marshland areas, at times alternating with dense woodland, where the drainage systems of important collectors such as Fossa Paltana, Fossa Berbegara and Fossa Monselesana, undoubtedly constituted opportunities for the aforementioned nautical connections on a local scale, given the objective difficulty in ensuring satisfactory transport overland, made problematic due to the frequent flooding and prolonged stagnation of water. During the Republic of Venice, after looking more attentively inland, the specific Magistratures then paid increasing attention to the inner lands and the internal set-up of waterways for navigation, in particular after overcoming the political crisis caused by the conflicts against the allies of the League of Cambray (peace of Bologna, 1516). Bearing this in mind, fluvial navigation emerged as the most effective means of solving and strengthening economic relations between Venice and its inland regions, involving not only trading powers of the Rialto markets or exclusive advantages for the land owners, but also the whole series of short range relations as mentioned previously. And it is here from the second half of the 16th century onwards there was a general revision of internal navigation. Implicit proof of this activity can be found in the special importance given to chorographic mapping of hydrographic elements, detailed on the maps with painstaking precision, also highlighting the role of the pre-eminent connection between the centrality of the lagoon and a prosperous and well-populated terra firma. If we focus now on the strategic position of Battaglia, it is worth noting that alongside its role as the fulcrum of nautical connections between the lagoon and central Veneto, with important routes towards the Po and itineraries to Lombardy, there was also an active concentration of water works. These were two important vocations marking out Battaglia as a typical non-agricultural rural centre, offering more opportunities for its inhabitants, attracting investments, while creating the foundations for frequent conflicts in the use of the waterways routed off from the canal of Battaglia. For example, one consideration is the continuity of navigation for fully laden boats needing adequate water flow, also to deal with the constant problem of silting. Due to the excessive number of water outlets required to run the mills on the canal Biancolino, on Seriola di Battaglia or on Bagnarolo, this meant serious difficulties for the transit of large burchio freight boats, impoverishing the capacity of the canal.

Some of the minor waterways flowing from the eastern slopes of the hills were used for the transport of trachyte stone and other stone materials obtained from the quarries. In an 18th century map by Poleni (A.S.Ve., Secr. Arch. Poleni, reg. 5, c. 56, entitled ‘Territorio a sud di Battaglia’, 1725), the canal of Lispida is depicted, identified in the drawing as ‘canaletto delle Pietre che va a Bovolenta’ (small canal of Stones running to Bovolenta – and from here towards the lagoon). From the captions integrating the drawing, we learn that initial means of navigation carrying stones from the quarries consisted in modestly sized boats (burchiella), suitable for the smaller water intake of the canal of Lispida (fig. 10). Once past the canal bridge, the burchiella boats berthed to small quaysides (referred to in the maps as porti) to transfer the materials to larger boats for navigation along the normal route towards Bacchiglione [Pergolis, 1989].

Now, if we consider river journeys for passengers, the canal of Battaglia may be seen as an attractive extension of the better known and more prestigious itinerary along the Riviera of Brenta, which concluded at the quays in Istrian stone in front of the monumental port of Portello, the most elegant point of entry to Padua. In fact, as will be seen in the following paragraphs, the canal from Padua to Monselice, from the second half of the 16th century, enabled passengers to make a comfortable and short journey to some of the riviera beauties gradually built as part of improvements to the lowland, including the eastern slopes of the Euganean Hills and the high banks of the raised section of the canal of Battaglia. The remarkable proximity to the hill ridges greatly enhances the riverside landscapes considered here, resulting in a highly attractive physical feature. The journey to and from Venice taken by land aristocracy clearly avoided the route towards Bacchiglione and the southern edge of the lagoon, not only due to its length and relative monotony, but also because it required strict control of the water flow, in particular using the technique of the butà, i.e. the programmed release of an adequate quantity of cubic metres to enable navigational descent of a convoy of burci.

2.2 Riverside villas and towns

If one can build on the river, it would be most pleasing and convenient; thus at little cost the boats may carry their ware directly to the villas, which will help the needs of the household and the animals, while the water would make the air cool in the summer, and create beautiful views. Thus both admirable and practical, the river would serve to irrigate the land, the grounds and the cottage gardens, which are the very heart and pleasure of the Villa. But navigable rivers cannot be had, and we shall attempt to build upon other running waters, moving away above all from the stagnant unmoving water, as this generates such unpleasant air.

[Palladio, 1570. Book II,. p. 45]

The quote of Palladium suggests a special aspect of countryside seduction, i.e. hydrography. During the pax veneta, across the entire terra firma, the placid flow of rivers, the bubbling spring brooks, the ordered layout of the drainage canals, the lively daily work of the mills, the navigation basins, the berthing quays for loading and unloading goods, are all situations in which water

makes an essential contribution to the cultural definition of ‘beautiful landscape’, thus in line with the century long tradition of landscape aesthetics [Dardel, 1986; Sorcinelli, 1998]. The manifold types of cultural appropriation of water, given the essential need for this product, undoubtedly constitute some of the most significant moments of man’s integration with nature. Following this, in the transition from feudalism to capitalism, the technical foundations were laid for an increasingly accurate and distributed modification to the relationship between earth and water, overcoming the restricted horizons of municipal localism that characterised the hydraulic interventions in medieval Europe. The effects of anthropisation, however, also facilitate more secure inhabitability of the territorial environments, in most cases by expanding the urban fabric and perfecting the transport network, both over land and by river. This involved both water management and river bed improvements. In 16th century Veneto, for example, there was the neoplatonic paradigm of natural harmony attained by the uniform separation of water and land features achieved by the implementation of drainage canals. This was the consolidation of a landscape that combines the classic tradition of pastoralism, the instances of Renaissance Arcadia and the lucid pragmatism of expanding land ownership [Ciriacono, 1986]. And here it is worth remembering once again the praise of Palladio for the fluvial sites and the construction of country villas [Cosgrove, 2000]. Water run-off regulated with basins, canals confined between banks, bordered by shady rows of trees, facilitated relations between the city and the countryside (and not only in the flat Venetian terra firma) and were also themselves harmonious features of the landscape, an occasion for leisure to enliven the souls of those walking along the banks, but also for those sailing through.

The specific events in the agrarian history of the Battaglia canal and the lagoon reveal significant examples of land investments, the results of which are clearly evident in terms of territory, also thanks to the building of noble residences around the area. The well-known phenomena of the country villas [Ackerman, 1992] in the Veneto region had a prestigious antecedent in the hillside residence of Francesco Petrarca at Arquà [Luciani, Mosser, 2009] accessible from Padua simply by navigation along the Battaglia canal through to the bridge-canal of Rivella [Bortolami, 2009, p. 135]. The subsequent spread of elegant homes over the pleasant slopes of the eastern side of the Euganean Hills constitutes a unique example among the various connections between city palaces and summer hillside residences, due to the fact that these villas could be reached directly by waterways, with the exception of a short ascent by cart road.

In general, the navigable routes, once mooring off from the urban quaysides, enabled passengers to reach a great number of country villas, sailing along charming routes in the lush countryside of the plains, enjoying the slow and comforting flow of the craft, so different from the rough journeys by carriage.

In the Veneto region in the second half of the 16th century these customary river journeys increased in popularity, above all among the aristocracy, investing more in agriculture, while also enjoying the parallel expansion of land reclamation plans, which in turn contributed to a more general and coordinated reorganisation of the waterways, especially on the lower plains.

Explicit references to a recreational use of the waterways, both in terms of leisure craft or as a selected means of transport to reach the rural ‘beauties’ on the terra firma, are found following consolidation of the pax veneta, after the second decade of the 16th century. Worth noting is the river route used by the Padua jurist Marco Mantova Benavides to reach his villa on the Euganean Hills of Valle San Giorgio. His town residence in Padua was close to the quayside of San Giovanni; from here, after loading his luggage onto the ‘boat to Este’, he started sailing ‘calmly ploughing through the transparent waves’ [M.L. Corso, S. Faccini, 1984, p. 271] of the Battaglia canal through to Monselice. Sailing further along the slow flow of the winding river Bisato, the route terminated at the quay of Rivadolmo. This was a berthing place of significant economic importance, where small freight boats known as burci were loaded with precious Mediterranean produce grown on the Euganean Hills, destined for the markets of Padua and Venice [Selmin, 1999, p. 47].

However judging from the considerable number of stately homes built between the 16th and 18th centuries along the banks or in the vicinity of the river route between Padua and Este [Verdi, 1989], it is evident that the role of the waterways met the recreational needs of that time. This reflected a common wish to return to nature and the pleasures of life in the country villas, with nostalgic and memorable locations, so dear to the Padua humanists, inspired by the proximity to the places where Petrarca stayed in the last years of his life. Contributing to this impressive expansion of elegant country homes there is not only the fortunate geographical combination of a pleasant range of hills, mostly bordering on a series of natural watercourses making for advantageous investments to improve the foundations of vast areas of marshland surrounding the Euganean Hills, but above all the fact that these territories could be reached along an articulated system of waterways connecting Padua, the hills, Venice and the southern area of its lagoon [Vallerani, 1983]. It is in this way that the medieval section of the Battaglia canal, joining Padua to Monselice, can be defined as an actual riviera, a real geographical ‘type’ indicating the apotheosis of anthropisation along a waterway [Marinelli, 1948, p. 68/2], while representing a rapid and profitable connection between the city and countryside and a decorative feature of the landscape widely used in the scenic construction for tourism resorts [Vallerani, 1989, p. 154].

The idea of the Battaglia canal as a riviera provides interesting connotations with similar anthropic layouts along the waterways of the rivieras of the Brenta and Sile. Though to a lesser extent with respect to the latter, along the raised section from Padua to Monselice, we can find a number of significant examples of noble villas, with facades overlooking the quays on the river banks. For example the villa Molin-Kofler (fig. 11), in the district of Mandriola, with a portico designed by Scamozzi stands on the left bank of the canal, on the site of the imposing Cataio and also at the villa Selvatico- Capodilista. In all these cases, iconographic and literary tradition (paintings, maps and etchings) celebrates the advantages of the river locations, underlining the scenic features of access to the water. Less resounding and more closely tied to the agronomic practice are the numerous stately homes and adjacent settlements found along the route of the Battaglia waterway down to the sea. The fluvial centres of Bovolenta and Pontelongo are particularly relevant here. It is especially worth mentioning the Benedictine court of Correzzola, a few steps away from the route of Bacchiglione, thus easily accessible navigating from Padua.

2.3 Protoindustry and cereal milling

The raised feature of the Battaglia canal, added to the presence of numerous intersections with drainage canals located on a lower level, represent advantages for the installation of water mills able to exploit significant quantities of energy over the many and notable differences in height. The water works can be considered among the most explicit indicators of the degree of anthropisation in a territory, highlighting the degree of control over flowing water. Many of these buildings can still be found today, deservedly classified as cultural heritage, are precious structural features enabling us to understand the evolution of the landscape.

On initial analysis these buildings benefit from the copious historical cartography dedicated to the town of Battaglia and its canal. Of particular interest are the maps drawn up to accompany requests presented to the Magistrature of Uncultivated Resources to install new water wheels or to upgrade existing water works. When delving further into the archives, these results can be seen to be great in number from the mid-17th century, not only due to the demographic recovery after the plague of 1630-1631, but also due to a substantial increase in the production of cereal crops due to the expansion of land reclamation. Among the many cases documented, we can see how the community of Monselice wanted to be granted authorisation to add a mill wheel in the area pertinent to Bagnarolo with water of the river Bisato in the same site where there are three further wheels [A.S.Ve, Beni Inculti Pd-Polesine, rot. 328, m. 1, dis. 4, 1656]. The chart drawn by Zuane Ciprian accompanying the petition and depicting the branch of the Bagnarolo canal (Fiume va à Pernumia, ‘the river flows towards Pernumia’), provides an interesting landscape, made up of roads running along the top of the banks, the watercourse (Fiume detto el Bizato va à Padoa, ‘the so-called Bizato river flows to Padua’), the water mill and other rural buildings, showing a profitable and balanced relationship between man and river (fig. 12).

Considering the historical centre of Battaglia, the wealth of documentation available provides a clear overview of the heritage of buildings and water products found still today, representing precious structural elements for the promotion of an adequate and stimulating ‘eco-museum’ dedicated to the evolution of the amphibious territory between the Euganean Hills and the lagoon. It is worth mentioning here the blocked terraced settlement structure distinguishing the ancient centre of Battaglia, and one of the most significant examples of ‘fluvial riviera’ of the Veneto plains [Vallerani, 2004, pp. 24-26]. A map by Alvise Scola of 1656 highlights the particular urban structure of Battaglia (fig. 13), stretching across the banks raised above the surrounding countryside [A.S.Ve, Beni Inculti Pd-Polesine, rot. 329, m. 2, dis. 10]. This drawing also serves to document the request for a change of activity, installing two mill wheels in the place of doi rode da guzar (blade sharpeners and other implements). The workshop is located on a modestly sized artificial channel (seriola) originating from the left bank of the canal via a small bulkhead.

In a later drawing (1686), produced by the surveyor Iseppo Cuman, the presence of workshops along this seriola intensified, demonstrating how the end of the 17th century saw a substantial planning on the terra firma of proto-industrial centres, mostly distributed along the waterways with adequate gradients (fig. 14). The map thus provides an image of the residential centre where craft trades developed (iron and copper tools) and the petitioning owner of the water intake, as indicated in the illustrative text in the drawing, plans to build a workshop for hulling rice and press linseed to extract oil.

In a cartographic document, produced by Stefano Foin in the second half of the 18th century (1776) and related to the southern section of the Frassine or Battagia canal, there is further confirmation of a widespread distribution of water mills around Monselice, Pernumia and Battaglia [A.S.Ve, Beni Inculti Pd-Polesine, rot. 331, m. 4, ds. 8]. The drawing also makes references to drainage work performed on the bed of the navigable canal between the waterfalls

supplying the water mills of Bagnarolo and Rivella (fig. 15). This excavation was useful not only for the transit of boats, but also to increase the supply of water and improve operation of the two important milling sites, one on the canal of Bagnarolo and the other on the branch of Rivella, both da quatro rode (‘equipped with four wheels’).

2.4 Agriculture and reclamation

Among the main objectives of these major environmental interventions, it is also worth mentioning the agronomic reclamation of vast marshland strips, creating an anthropised countryside. This involved design and operative phases, and subsequent physiological results that went beyond the mere production environment and residential areas, extending to the cultural processes of symbolic elaboration that justify, celebrate and explain the role of the community in their natural evolution. The result is thus a complex and motivated rhetorical discourse in perfect harmony with the ruling classes, clearly evident above all after the second half of the 19th century, when technical progress, encouraged by the frenetic dynamics of the industrial revolution, enabled increasingly more ability for transformation, hitherto unknown, of the natural basis [Cosgrove, Petts, 1990, p. 6].

The waterway was soon to be redefined, especially following the progress in European hydraulics, to become an attractive background to the traditional charm of country life. In addition to this, the fluvial element confirmed its remarkable iconic value within landscape painting, starting with the Veneto and Flemish painters of the 16th century [Gibson, 1989] promoting an evocative and formal language of harmony and serenity, still today widely appreciated and practised among the infinite numbers of bourgeois landscape paintings promoted

by the media. Praise of the countryside thus hastened to be identified with the controlled distribution of natural watercourses, integrated by an increasingly complex network of artificial canals, stable settlements and berthing points.

As regards works to improve the river beds, differences exist according to the morphological context at the foot of the eastern Euganean Hills and the progressive descent of the slopes towards the final sections of Bacchiglione, Brenta Nova and Novissima. While in the lowlands upstream of the lagoon efforts concentrated on the drainage work of the amphibious land, the technical choices for drying out the land in the vicinity of the lagoon were subject to the inflexible demands of Venice aimed at preserving the lagoon. This strategy conflicted with the objectives of those promoting the drying out of the low pre-coastal land, clearly evident in the practical action and writings of Alvise Cornaro, a powerful Padua man who was undoubtedly one of the main actors during the first half of the 16th century in the agricultural rebirth of modern Europe [Puppi, 1980]. He was attributed with the promotion of an innovative ideal of rural landscape in which the Arcadian atmospheres blend together to consolidate into more concrete and less aesthetic praise of life in the country, resulting in the drafting of a brief treatise on the vita sobria (sombre life) written by Cornaro towards the end of his long life [Fiocco, 1965, pp. 171-190]. As a consequence his estates not only remained foreign to the humanist view that aimed at the creation of pastoral or Arcadian sceneries, but also, at least to a certain extent, to the view of the countryside as a place of retreat for cultural otium and contemplation. To the west of the Battaglia canal between the hills of Galzignano and Monselice, after the mid-16th century, numerous interventions were started for draining stagnant water that prevented profitable farming: this was the retrato de Monselese, among the first consortia of reclamation set up in this territory (1557). The substantial archive documentation and cartography enables a satisfactory reconstruction of the environmental frameworks, thus enabling the draft of an accurate survey of subsequent developments leading to the current layout of the landscape. An evident example can be found in the estimates regarding the above mentioned retrato and the book of rentals of property owned by the Selvatico family within this consortium limits. These show that, while at the start of the 17th century [A.S.PD, Estimo, 1615] the land was still subject to frequent flooding (with the consequent build-up of stagnant water), towards the end of the same century the rental contracts then indicated a consolidated presence of planted up land, in other words fields bordered with rows of trees, vineyards, stable pasture land and cereal rotation crops [A.S.PD, Fondo Selvatico, b. 1261, ‘Affitto del 1694’].

This improvement to the quality of farming land can also be found towards the areas of Conselve and Piove where, still following the technical and organisational indications promoted by the Magistrature of Uncultivated Resources, further consortia partitions were identified following the act called terminazione in Pregadi of 23rd June 1604 for the preservation of the lagoon; these are Monforesto, Sesta Presa, Settima Presa Superiore and Presa Inferiore (fig. 5). From this environmental context, worth special attention are the fixtures of Sesta Presa, also thanks to the eloquent testimony of the land register drawn up by surveyor Paolo Rossi in 1675 (recently digitalised), where the cartography is accompanied by an accurate description of the quality of the land, property, providing ‘with incredible precision the layout of the water and land of the entire area’ [Grandis, 2000, p. 61].

In the Napoleon Era, with a Royal Decree of 6th May 1806, the authorities attempted to simplify the fragmentation of the extension of consortia, incorporating them in larger territorial divisions, known as ‘Circondari’. The setup of these bodies aimed at simplifying coordination of interventions related not only to the drainage of land, but also the maintenance of river banks on the main watercourses, and prevent the risk of collapse during floods [Sanfermo, 1810]. With the return to Austria, hydraulic management was assigned to individual consortia, no longer referring to the ‘Circondari’. The most relevant event in these first decades of Austrian administration is undoubtedly the decommissioning of the Brenta Nova, already subject of a long debate at the time of the Arctic Plan (1787) due to the increasingly shallow depths of the canal [Donà, 1981], making it unusable for running off flood water or for transit. In its place, the new channel from Stra to Corte was laid, completed in 1858.

It must be remembered that the straight section of the Brenta Nova served as a border between the consortia of Sesta Presa, beyond the right bank, and Settima Presa, beyond the left bank and, following the disastrous floods of 1882, constituted a serious obstacle to the downflow from the land of Sesta Presa. The same critical aspects are still evident in a consortia report of 1889 [A.S.V., Fondo Genio Civile, b. 933], although this also states the fact that the presence of abandoned river banks constitutes a substantial protective barrier, defending the crops of the Settima Presa from any flood water descending from the west. The provisions to restore reclamation of the low plains considered here included a revision to the route of the canal named Cornio di Campagnalupia, and the building of a water works system at Santa Margherita di Codevigo on the drainage canal Schilla, for the run-off of water from the lower border of Sesta Presa. Settima Presa Inferiore was added to this latter consortium in 1940, known for the predominant presence of land below the average sea level and ‘dried mechanically by means of a water works system located beyond the Canal Nuovissimo in the area of Vaso Cavaizze in the municipality of Codevigo.’ [Aa. Vv., 1974, p. 287].

Other important authorities in charge of the drainage of the southern areas were the consortia of Monforesto, Bacchiglione-Fossa Paltana and Foci Brenta-Adige, which on 6th March 1972 merged to become the Bacchiglione-Adige land reclamation authority, whose drainage work reaches the right bank of the Bacchiglione, main landmark of river navigation. In this regard, we cannot fail to notice the extraordinary complexity of the progressive accumulation of drains, channels, and ditches toward the east, channelling waters to the impressive dewatering facilities of Barbegara and Civé. These in turn connect to an infinite network of additional segments used not only for the prevailing drainage needs, but also for the reverse and increasingly urgent requests for irrigation. We are thus faced with an amphibious landscape where anatomy and physiology are closely linked to intensive agricultural production and relationships with navigation were inseparable until the middle of the last century. This is especially the case of the riverside locations of the Pontelongo, Cagnola, and Cavarzere sugar mills and of the imposing grain-grinding building in Battaglia, all fundamental economic centres that profited from the presence of an active river fleet (fig. 16).