RECOVERING WATER MEMORIES AND SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

Documented in detail by archives and objects scattered along the banks and in the vicinity, the effective evolution of hydrography can provide additional information to supplement the stories of those who have long experienced the changing coastal landscape. While researching water memories through fieldwork and with the aid of historical geography and cultural anthropology methodologies, it becomes increasingly difficult to detect the vestiges left by centuries of land and water development throughout the intricate network of natural and manmade waterways running through the lower plains touching on the Brenta and the Bacchiglione. Scientific work in this context entails the analysis of environmental frameworks that have witnessed the consolidation of major river routes in addition to the unravelling of minor routes that connected scattered houses and small villages during the long process of building agricultural landscapes over land slightly above sea level. It involves opening one’s eyes onto what remains of a cultural and environmental heritage left in the shadows, neglected, nearly functionally extinct, fading from memory, almost a ‘holocaust’ due to the overwhelming onset of different economies, activities, and perceptions.

This sad downhill slope of obsolescence seems perhaps less dramatic in some specific situations, as is the case of a handful of competent and enthusiastic volunteers offering their constant and worthy commitment within the confines of the Battaglia Terme Museum. These people have set themselves the existential objective of retrieving the cultural components that tie the most diverse hydrographic elements such as rivers, lagoons, and lakes to their riparian communities. The generous efforts of the guardians of water memories [Jori, 2009; Mainardi, 2012], some of them authentic river rhapsodists, have been matched for a long time now by researchers from academia as well as local cultural institutions. Thw work of these researchers has provided a rich bibliography, not always readily available, which expresses a stimulating cultural vibrancy, restoring significant land and river knowledge centred not only around navigation and boat building, but also related to studies of areas such as fisheries, ports, and the dynamics of riverside settlements.

4.1 In defence of river stories

The end of commercial navigation along Veneto’s waterways brought with it the disappearance of some specific professional groups such as boatmen, horse-keepers, shipwrights, wheelbarrowers, and basin operators, similarly to other riparian figures such as washerwomen, fishermen, plowmen and sand diggers engaged in the then tolerable removal of aggregate from river beds [Boscolo, Gibin, Tiozzo, 1986]. In order to achieve satisfactory results from this type of analysis, one must rely both on our large photographic heritage and reports from local history. These should be augmented by the archival documents found in the Civil Engineering Department and/or land reclamation consortia files, little explored and uncatalogued gold mines of memories often facing the nightmare of being dispersed or reduced to pulp like any other trivial waste, though ennobled by the virtuous practice of recycling. But without a doubt, the primary source of information that is most active and generous in detail and nuances is the powerful narrative of people from this very land, who provide irreplaceable valuable testimonies in the attempt to reconnect social contexts torn and scattered by the indifference of man and time.

Up until a decade ago, a sizable group of former boatmen were able to tell their tales and help reconstruct navigation events regarding the Battaglia network. Their vivid memories provided a wealth of valuable oral sources to gain detailed information about life on board the boats, nautical skills and manoeuvres, and the names of boat equipment and items, all of which made possible the collection and protection of their peculiar sailor lingo. Here, it is suffice to mention the main narrative topics that we managed to extract from the boatmen, together with the principles according to which the numerous objects preserved at the Battaglia Museum were organised.

According to the model employed by most publications regarding Veneto’s inland navigation and boatmen, navigation itself appears as the first and foremost aspect. Here, ethnographic studies focus with special reference to the mechanics and names of manoeuvres, comparing specific propulsion modes to river and lagoon borne morphologies. These include the use of long oars for mooring manoeuvres and boat steering when in a downward current flow, towing with horses, and sailing, especially in lagoon environments and along the ends of rivers, where riverbeds expand. Naval museography requires that prominence be given also to shipbuilding, caulking, hot bending of metal plates, line preparation, small and diversified repair jobs that occupied boatmen during periods not on the water, and different loading techniques according to the type of goods. Another topic that greatly stimulated the evocative power of memories was simple everyday ‘life on board’, which evinced a close symbiosis with one’s boat, as both one’s home and working tool, and in some cases even as one’s cradle and hospital, thus triggering feelings of deep intimacy and identification.

Among the precious documents preserved in Battaglia’s Museum of River Navigation, there is an abundant wealth of audio cassettes filled with hours of recordings of the last boatmen’s stories (Marchioro, 2003). This collection of oral histories organised by date and topic has been occupying some dedicated scholars and graduate students. This provides a good starting point for further investigation, and most of all for the preservation of the living voices belonging to the last players in the history of river navigation. Along with the Museum exhibition, the above indicates the general will to face oblivion and lay the foundations for the preservation of an important aspect of terra firma culture.

Collecting these accounts allows the pride for the land and water of the former boatmen of Padua’s lowlands to shine through, currently well represented by Riccardo Cappellozza, an authentic and tireless ‘retriever’ of memories, as Mario Rigoni Stern would say. For decades, Capellozza has felt that his vocation is to defend the memory of this activity and often likes to say that, ‘it is impossible to remember all the places I have searched for concrete evidence of ancient navigation. It has been like repeating all the boat journeys I had taken in my youth but on dry land, looking for the people and docks I knew, visiting basin keepers, and stopping in taverns for a drink as I once did. I walked the banks, stopping where I found old hauled boat, trying to salvage what I could. Out of all this research, I recovered valuable photographic material and manuscripts, but also boats, onboard equipment such as blocks, sails, lines and rudders, and boat building materials’ [Vallerani, 2009, p. 8].

Luciano Rosada is certainly another prominent figure among former boatmen, who contributed greatly to limiting the loss of river navigation memories. His nautical memory intersects with a special proclivity for painting and writing poetry in Padua dialect (fig. 20). His spontaneous creativity focuses constantly on fluvial navigation and its environments, and is able to communicate the existential intimacy of life on board as well as his relationship with the world within the river banks, the flow of water. This boatman-poet often uses the demise of fluvial navigation as a metaphor of human decline, an old barge pulled ashore and left to rot is likened to a living body falling apart after having lived through one too many experiences. Other related themes are the eternal flow of the currents and the final transition to the other side, after struggling to crossing the middle of the river, where the eddies are strongest and most threatening and the shoals most treacherous (Rosada, 1979).

4.2 New attitudes

Since the 1980s, a new, shared sensitivity has emerged from the need to retrieve the quality of the environment, to reevaluate specific geo-historical landmarks on all levels, and research among the complex vestiges left in the landscape to find concrete signs produced by economic and residential choices and the organisation of natural morphologies. This new approach has equipped itself with tools that are critical for coping with the relentless erosion of cultural heritage, intended not only as simple objects of value, but above all, with the landscapes that serve as their background. This general observation engendered an awareness of the extraordinary interest evoked by the morphological and cultural contexts pertaining to water landscapes, be they lagoon, coastal, lake, or river areas. The impressive extent of the hydrographic network of the Venetian hinterland soon revealed the valuable potential for a successful renewal of land development dynamics, which led only in part to an actual improvement of the greater urban areas, to a status of the so-called ‘sprawling city’. Naturally, there have been significant episodes of conscious and durable recovery of large fluvial sectors, to the extent that being defined as a ‘water town’ is now deemed a prestigious award by several municipalities. In this respect, action has been applied along not only urban hydrographic stretches, but also fluvial waterways connected to prestigious buildings, as well as rural villages (fig. 21) and settings not overly compromised by land use.

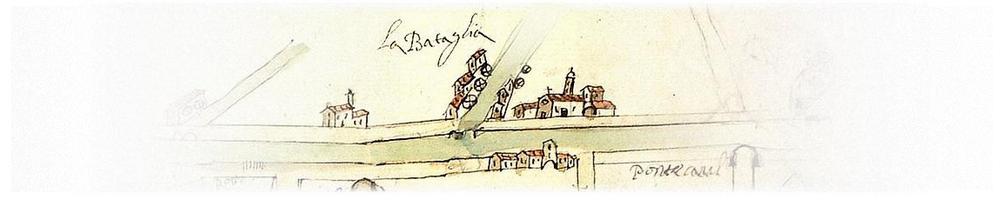

Along these lines, the Battaglia canal should be considered an environmentally valuable hydrographic segment for its harmonious synthesis of semi-natural elements and historical/artistic assets. It was also created by man in the Middle Ages and could therefore be made part of a broader strategy aimed at the recovery of Europe’s historic waterways. In fact, the whole of Europe is an endless repository of water-related stories simply waiting to be re-evaluated, surveyed, and carefully catalogued, to deal with the silent and hidden impoverishment of a significant aspect of this continent’s cultural heritage. Here we refer to the boats and boatmen that for centuries have sailed and lived along the banks of the tens and tens of thousands of kilometres of a close-knit hydrographic network experiencing the events that changed the landscapes over this millennia. As mentioned earlier, narratives of land and water-related events may be considered as an indisputable heritage and reference point in protecting of local characters themselves, as well as old docks, boat repair yards, mills, bridges, and riverside pubs. These all constitute vital material requiring all our attention, to avoid wasting the precious memory of a secular and fruitful relationship between humans and waterways.

However, boats, the most important elements of European nautical history, run the highest risk of becoming extinct. Examples in this regard are the half-sunk small boats used to house crawfish river traps in the bends of the middle Brenta until a few years ago, and those pulled ashore and left to rot in the sun and rain on the banks of the Bodrog just before flowing into the Tibisco. Additional examples of the great wealth of river-faring vessel types responding to specific morphological and hydrographical conditions are found in some old and rare photographs of riverboats from Lake Nemi, such as a rebuilt raft commemorating timber transportation along the Piave, and the rafts still used for the same purpose along the upper and middle Tara (the right-hand tributary of the Drina in Bosnia).

A recent international conference held in Battaglia Terme and the Venice headquarters of UNESCO in October of 2012, stressed the need to establish cooperative relationships with major European museums. The latter institutions, very active and culturally prestigious, were more than willing to lay the working foundations for future conferences and agreement protocols with the Museum of Battaglia Terme, with the aim of finally implementing an international network devoted to the study and preservation of river communities. Despite the objectively grievous current economic difficulties, shared cultural attitudes are certainly ripe for a better appreciation of the Battaglia Museum, in part already active within the European exhibition network.

However, the development of this essay also provides an opportunity to consider the ramifications of the river routes toward Este and the lagoons, in the wake of growing interest in marginal geographical realities and lesser-known sections of rural lowlands. Our aim is to act upon prejudicial indifference towards reclamation landscapes, whose unsuspected ecological, historical, and monumental attributes cannot escape a discerning eye (fig. 22). The current consolidation of new perceptions and assessments toward lesser known and popular landscapes also involves local administrators, who have been increasingly more attentive to the identifying features of their lands. This holds true for both their quality products and the value of their ‘culture,’ thanks in part to the publication of several books accompanied by accurate and comprehensive photographic commentaries.

4.3 From sailor lingo to the museum

A photographic exhibition organised at the Battaglia Terme city library in June and July of 1979 proved to be a turning point in the process of protecting mainland nautical culture, ‘Thousands of people visited the exhibition. Such resounding success inspired the idea of a book that would illustrate the meaning and significance of navigation, as a way to salvage at least the words and images of such a fascinating way of life of our people.’ [Sandon, 1984, p. 60]. The then large number of former boatmen who took turns in explaining to visitors the events depicted in the photographs made use of a lexicon alien to most. Therefore, the need became obvious to collect the vanishing terminology that reflected the remarkable complexity of inland navigation. Long conversations with the boatmen while looking at the photographs, objects found in old building sites or recovered from dark garages and cellars, were instrumental in bringing back hundreds of terms related to life on board and navigation, which led to the publication of a catalogue detailing the photographs on display along with a sizable corpus of sailing-based terminology. [Aa. Vv., 1980].

The logical study of these precious oral sources triggered a domino effect that led to an even deeper analysis of recondite memories and the further recovery of navigation objects such as rigging elements, manoeuvring blocks, shipyard carpenter tools, curve templates for ordinates, lines, specimens of rudders from boats now destroyed. A veritable heritage of material culture accumulated in a short time that otherwise would have fallen into oblivion and would not have been properly handled if simply stored in a warehouse. [Zanetti, 1998]. The leading role played by boatman Riccardo Cappellozza, whose research activity is mentioned previously, came to the fore at this time.

Despite the obviously urgent need to collect as much material as possible (a process that unfortunately met with failure when attempting to salvage boat specimens), considerable attention was also paid to interdisciplinary initiatives that promoted historical, geographical, anthropological, and dialectological research, yielding a large number of currently available publications that deal in the reconstruction of historical, environmental and social developments regarding Battaglia and its canal. Thus, the presence of a museum stimulated the study of the close relationship between the specific items preserved and the socio-economic context that produced them. It was clear from the beginning that objects alone would not have been enough to make a museum, and that, ‘an all-out recovery strategy imposed by the fear of losing materials’ should be matched by, ‘a rigorous analysis of the recovered items that would include their use, the know-how and manufacturing techniques used to produce them, and their socio-symbolic context’ [Mondardini Morelli, 1988 p. 91].

Another important and attractive prospect is to extend the museum effect to Battaglia Terme’s historical centre, bringing back the legacy of its urban planning and enhancing its tourism, thereby reawakening dormant synergies with the extraordinary potential represented by the local hot springs. In this regard, the creation of a river/hill eco-museum that would involve the prestigious heritage of Veneto’s villas and rural buildings, could lead to a higher quality landscape that would contribute to a more pleasant stay for patients, whose idea of well-being has been evolving beyond specialty healthcare into a holistic approach that includes visual contentment and residential satisfaction. Foreign spas have met with success thanks to environmental quality, a feature sorely lacking in the chaotic, ramshackle and poor planning of nearby towns of Abano, Montegrotto, and Galzignano.

Good ideas for a fruitful interaction between urban renewal and open-air museum networks should be inspired starting right from the centre of Battaglia, which features impressive canals connected by a bridge of apparent Venetian inspiration. It should also be noted that the Museum building, once the municipal slaughterhouse, is located at the end of the Ortazzo river banks, just downstream of the old mill port and the village built along the ancient seriola, a short water supply point that used to power numerous water wheels; undoubtedly, a top-quality urban/fluvial context.

Another perspective able to qualify Battaglia’s identity would be the establishment of an inland navigation cultural centre (fig. 23) that would be relevant to European history, by using operational contacts with similar European institutions (Canal de Bourgogne, Canal de Castilla Canal & River Trust, Stoke Bruerne Canal Museum), promoting educational exchanges and tourism, and related to agritourism including the entire Adige/Brenta waterway network as well as Parco Colli.

The Museum of Battaglia thus stands as a pivotal hub for the enrichment of an identity that expands throughout Veneto’s lowlands and even further within a broader European cultural movement, aimed at the educational and touristic rehabilitation of the ancient waterways that went out of service following the decline of commercial navigation. Similar initiatives throughout Europe, Spain’s Canal de Castilla, France’s Canal du Midi, Ireland’s Royal Canal, England’s Grand Union Canal, Sweden’s Göta Kanal, Germany’s Finow Kanal, would lead to enlightened planning engaging the broader regional contexts characterised by the vast and ancient fluvial networks employed by man, as is the case of Veneto’s lowlands. This new project would aim at rebalancing the geo-economic arrangements responsible for the considerable waste of resources and environmental degradation that has occurred in the recent past. Within this perspective, museum institutions entirely similar to Battaglia’s have been playing a primary role in recovering the memory and dignity of ancient ways of existence and complex fluvial skills, with the purpose of transmitting them to new generations and political and technical government bodies.

4.4 Opportunities for sustainable tourism

The issues discussed so far have shown the importance of Venice’s inland nautical heritage. We should now mention that current times are ripe for broadening the awareness of waterways with regard to their touristic and recreational value. The world of advertisement reveals an increased popular appreciation for fluvial environments insofar as they provide ideal settings for sports and games as well as excursions of a more cultural nature. Hydrographic atmospheres belong mostly to a landscape that eschews urban developments centred on land based traffic, which is not just true of Veneto. The previously mentioned definition of waterways as ‘cultural corridors’ is rather suggestive of manufactured items related to specific hydraulic functionalities, but also of refined homes, places of worship, farm houses, and taverns.

Abandoned for the most part, the old water mills observable have become significant elements of the hydrographic landscape. Many of these buildings have become landmarks for tourism along European rivers, even being transformed into thematic museums that extend beyond the buildings themselves to the surrounding environment, typically including the recovery of gates, bridges, and piers with moorings for pleasure boats. In countries such as Britain, France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany, the established practice of tourist travel along inland waterways, or ‘cultural corridors,’ has stimulated the recovery of almost all the basins necessary to fluvial navigation, and encouraged new businesses dealing with the reopening of old river inns, thereby facilitating friendly and lively encounters among land and river travellers.

Ours is a case of niche tourism, and therefore it is all too obvious that there is no need to forecast future overcrowding due to mass tourism, defined by European academics as the ‘landscape devourer’.

The growing importance of leisure time is another essential point of reference within the framework of a changing post-modern popular perspective, increasingly aware of environmental issues. The region lying between the Euganean Hills and the lagoon has inspired a vast wealth of publications that present an adequate image of a stretch of land whose individuality is to be sought in a geo-historically developed morphology. These landscape elements constitute a precious natural, historical and cultural heritage, which could encourage the creation of an indisputably valid touristic and recreational system, especially when considering the picturesque fluvial waterways running from the hills to the sea (fig. 24).

However, one cannot help but notice a worrying deterioration in the quality of the landscape, especially along the main road connections. Countryside urbanisation is an all too familiar and controversial issue that must be taken into account when considering land redevelopment. Matters concerning fluvial tourism should be addressed with strategies aiming at the strict safeguarding and restoration of the natural environment, not only by re-establishing balance, but also by generating ways to satisfy the growing demand for pleasant leisure spaces. Rather than tourism per se, we should perhaps be looking at recreation, in the sense of opportunities for city dwellers (from Padua, Mestre, Monselice, and Riviera del Brenta) to relax and regenerate physically and psychologically at any time of day and in any season (except, within reason, for cases of extreme weather).

We mention below a few potential sustainable tourism applications with regard to the many recreational opportunities provided by the location of the area under consideration:

▪ literary tourism following in Petrarca’s footsteps;

▪ thematic trails: churches, river villages, villas, reclamation landscapes;

▪ river excursions (by means of indigenous watercrafts and light boats);

▪ Millecampi valley;

▪ agritourism and hotel facilities derived from sets of historic buildings;

▪ bike and horseback riding;

▪ local food and wine routes and tastings.

The options set out above emphasize the attractive potential and prospects for nautical tourism possible within the context of environmental sustainability, consistent both with the hydrographic ecosystem and with the cultural stimuli offered by riparian landscapes and the local cultural vestiges offered by the Battaglia Museum. We refer here to the use of local watercrafts, both for individual (ditch hoppers and Venetian style rowing boats) and collective traveling experiences (recovered burci refitted for group transportation). By local watercraft we mean a type of boat used in some cases until the recent past within a limited river, lake or lagoon area and specifically built for such purpose. For example, small flatbottomed boats named saltafossi (‘ditch hoppers’) were operative along minor water courses such as the Bagnarolo and Biancolino canals and lowland drains. On these the boatman would make use of a pole while standing, making it possible to navigate in shallow water and also against the current; a single man would suffice for hauling manoeuvres, given the size of the boat. Similar to the saltafossi, the pantane of the upper Sile (fig. 25) are a significant example of recovery of this traditional propulsion technique, as many new specimens have recently been built for recreational and educational ends [Michieletto, 2009].

Promoting the use of indigenous watercrafts should go hand in hand with the re-qualification of river landscapes. Along these lines, boats are reclaiming their role as elements of fluvial culture amenable to recreational practices. It would be a matter of offering specific courses teaching pole-driven propulsion techniques, not unlike what is happening in the Venice lagoon and other rowing inland clubs, following in the wake of numerous initiatives spreading the practices of Venetian rowing and lug sailing. In the case of Venice, inevitably significant due to this city’s global appeal, the number of indigenous watercrafts employing traditional propulsion techniques has been growing beyond the usual competition framework, pursuing alternative forms of recreation. Ultimately, it would be a matter of promoting novel recreational approaches, encouraging this specific boating-for-fun niche in order to achieve a successful synthesis between sports/recreation and the pleasure of recovering ancient forms of water travel, satisfying also a cultural interest for traditional nautical skills.

As a result, with these objectives clearly in mind, inland navigation museums and cultural associations could transform into cultural hubs for the spread of an innovative awareness of recreational navigation on board indigenous watercrafts for the transportation of individuals or groups. Taking again as an example what has been achieved in Battaglia Terme, the site of the Museum is geographically strategic in relation to any potential river tourism routes, since it connects to the historic towns of Padua, Monselice, Este, the Riviera del Brenta (and from there to all eastern routes up to Treviso, Pordenone and the Friuli), Chioggia, and the southern lagoon (with subsequent connections to the Adige and the Po). The opportunities for berthing adjacent to the Museum building are already in part used by a number of boats, testimony to the recent past of inland navigation, and one of these vessels has been converted to carry passengers, as part of plans to expand river cruising, for cultural and educational purposes. Meanwhile, as regards individual boats and the museum activities, courses in Venetian rowing or ‘pertica’ techniques could be introduced, where possible making use of local rowing experts and resources, or traditional rowing boats could be hired out, thus restoring activities of the minor shipyard skills on land, once so popular and widespread across the Veneto plains (fig. 26).

The prospects outlined here to promote the tourism vocation of this area should obviously not only aim at the increase in the number of visitors, but, as recently mentioned, should also be intended to deal with the increasing demand of residents to improve the quality of day to day living. The humanisation of living space does not only mean taking care of the physical locations, but also finding the means to satisfy the local population, retrieving the age-old pleasures of social village relations, and encourage a sense of being settled. The concept of humanising daily life is also closely tied to an increasing interest in personal and local areas, and the surrounding landscape with its unique and historical environmental marks. Being aware of this is already a good first step forward; the next will be to return to being travellers ‘outside the gate’, content to live among the Euganean, Brenta and Bacchiglione hills, and the southern side of the Veneto lagoon, and thus start, together with the current commitment of the Pro Loco associations, promoting and protecting this inherited remarkable territorial heritage (fig. 27).

The final hope and aim is the co-existence of recreational use by local residents and the tourism supply for visitors, while emphasising that these vocations should be able to achieve what is normally defined as ‘innovation’, a strategic key word, rather obsessively coined in the recent years of general economic decline. Real innovation lies in giving due importance to the landscape heritage, the quality of water, the condition of green areas, local agriculture, traditional food and recipes, a slower pace of life, and re-evaluating the knowledge of the elderly, all capable of increasing the ‘competitive edge’ (yet another key phrase of recent years) of an area, measured also in the satisfaction of residents, in a healthy environment, protecting the tangible assets of the land. The case of this part of the lower plains could therefore be seen as a testing area where the well-known approach of participation can be encouraged, in order to demonstrate which and how many advantages can be drawn from the conscious re-weaving of relations between the community and the land.

Francesco Vallerani